EASY POKER

EFFECT

A spectator selects five cards from the pack and is asked to imagine that it forms a perfect poker hand. Well, perfect except for one card. One card won’t help him win. Which card would he like to discard?

Without looking at any of them he discards one of the cards, say the two of hearts. He turns the remaining four face-up and discovers that he has the ten, jack, queen and king of clubs. Somehow he managed to get rid of the one that didn’t fit.

But can he find the card he needs to make a royal flush? He selects another card from the deck. Incredibly, it is the missing ace of clubs. What a guy!

METHOD

This is a solution to a poker problem that Fulves wrote about in Pallbearers Review. Check Francis Haxton’s Gambler’s Last Chance (Vol 2, No 10) for a similar effect.

There are many ways to approach the effect but this has the benefit of being almost self-working. The disadvantage is that it uses a double-back card.

Have the double-backer on top of the deck and below it, in no particular order, the royal flush in clubs. These five cards should be face up.

Begin by giving the deck a false shuffle bringing the set-up back to the top. Then slowly dribble the cards from the right hand to the left as you ask a spectator to call stop.

He does and you halt the dribble and drop the right hand cards face-up onto the left hand packet as you say, “We’ll cut the pack where you said stop.” This is a handling of the Christ Force.

Spread the face up cards into the right hand. “You could have stopped anywhere.” And divide the pack so that all the face down cards are in the left. Deal the top five cards face down onto the table. “But you stopped here. Let’s take the next five cards.”

Replace the right hand cards face-down under the left hand packet.

“I want you to imagine that you have just been dealt a poker hand. Not only that but it is a very good poker hand except for one card. One card spoils the hand. Which do you think it is?”

Since the cards are all face-down, he can only guess. Get as much fun as you can out of him picking one of the five cards. Then pick it up and place it face-down on top of the deck. Immediately execute a triple lift and push the face-up card that shows off the deck.

By the way, you can get a break ready for the triple as the spectator is choosing one of the tabled cards.

Whatever card shows, refer to it in some meaningful way. You might find he appears to have discarded a low value card. On the other hand it might be an ace. Make the most of it, then replace it face-down under the deck.

Because of the triple lift a club card now lies face-up under the double backer.

“You’ve got rid of one card. Time to choose another.”

Repeat the Christ Force, this time pushing a single card onto the table. For the moment keep it separate from the other four tabled cards.

Time for the finale. Turn over the first four chosen cards and reveal them to be almost a royal flush. Then turn over the remaining chosen card to show that it completes the hand perfectly.

That’s it. It is actually quite an economical handling. The real skill lies in making the effect clear to the spectators. They choose a poker hand, discard the odd card and find its replacement. Try experimenting with different presentations to find the approach that works best for you.

From the point of view of method it’s quite cheeky in that as soon as they have discarded one of the original five cards you force it right back on them!

Thursday, August 31, 2006

Sunday, August 20, 2006

SECRET OF THE CARDS

I remember the moment very clearly. I was at the office of Martin Breese videotaping Basil Horwitz as he demonstrated some of his material for a forthcoming book. This would have been in the mid-eighties.

Basil had dealt some ESP cards onto a table and I was looking through the viewfinder on the video camera. Then I noticed something very odd. I stopped filming, went over to the table and took a good look at those cards. They appeared perfectly ordinary, it was a pack of ESP Cards manufactured by Haines House of Cards in America. So I went back to the camera and looked through the viewfinder again and it was like looking through a pair of magic spectacles because I could see marks on the backs of the cards. I stepped away from the camera and looked at the cards again. To my surprise I could still see the marks.

“Basil, pick up those cards and give them a shuffle,” I said. Basil did, he knew I was up to something but couldn’t figure out what. “Now deal them in a row.” Five cards went face down onto the table. “Now turn the one on the right face up. It’s the star.” He did. And it was. And all the time I’d been standing a dozen feet away from him.

What I’d discovered, quite by accident, is that the Haines’ pack of ESP cards is marked. I’m not referring to the tiny markings at the corners, those are quite well known, but two big broad strokes on the backs that can be read across a room. In fact, here’s the peculiar thing. They can only be read across the room. Go up to the pack, examine the backs of the cards and I promise you you’ll never find those markings unless you know where to look.

Some years later, I mentioned this to magician and mentalist Ray Hyman on the phone, saying only that the Haines cards were marked. It’s a one-way mark, which is how I knew where the Star was on that table. I’d noted that its back was the wrong way up compared to the others. Anyway, Ray was coming to England to appear in a television documentary, and I met him at the airport on his arrival. First thing he did was bring out a deck of Haines ESP cards and ask where the hell the marks where. He’d been examining them on his plane journey and just couldn’t find them. But that’s the beauty of it. Look at the cards up close and it’s impossible to spot them. Put the cards on a table across the room, and they are as clear as day.

Enough of the teasing. The marks are the result of a flaw in the spacing of the tiny stars on the back of the cards. It produces two broad strokes across one end. And you can only see the strokes at a distance. I’ve tried to illustrate the position of the strokes in the diagram (1). Both cards have the marks at the same end, but I’ve highlighted them on the second card. They are impossible to see in the first card because of the reproduction process but if you had the real cards in front of you, you would be able to pick them out. Dig out a pack and try it for yourself.

As soon as you get near the cards, the markings disappear from sight, which means you have to be careful when sorting them into a one-way arrangement. Reading the cards up close is an acquired skill. Reading them from a distance is much much easier.

As for applications, well like names of the Devil, they are legion. Set up a pack in the usual Circle, Cross, Lines, Square, Star order. Have every Star arranged the wrong way and you have a stacked deck you can read across the room. Someone can cut and cut and deal four cards onto the table. You immediately know their order (if no Star appears, obviously you have the other four cards). From here, miracles can be worked.

The best kind of effect is one in which you stand well away from the spectator and the cards. A hands-off routine, possibly working with two spectators sitting at different tables, as they would be if involved in an old Duke University telepathy test. It’s a scenario that gives you a good excuse to use the cards. Have the spectators sit back to back, so that they can’t see each other. You, of course, can see all the cards as they are cut and dealt and you’ll find it easy to bring about remarkable coincidences just by controlling their actions and introducing one or two instances of Magicians Choice. I’ll leave the rest to you.

NOTES: This item was originally contributed to Trevor McCrombie’s online magazine The Centre Tear. As several readers proved, the marking system can be used in a variety of ways. So have fun!

Friday, July 07, 2006

A TRICK FROM ERIC MASON

Twenty years ago the late Eric Mason devised an effect called Stigma. It was an original idea involving the number and suit of a named card appearing as blisters on the performer’s fingers.

As similar effects are now coming onto the market I thought you might be interested in Eric’s original, taken from the notes and illustrations he gave me on 1st August 1986. They are only notes, not a full step by step description, but they should be enough to get a good idea of how Eric approached the problem. What a farsighted genius he was.

STIGMA by Eric Mason

To impress with any card called for! Ask the spectator to think of a card and visualise it as a large image and then to mentally compress it down to say approximately a half inch size. Reaching forward to confirm you pluck the image from its moment of time and space – your fingers appear to BURN! Gosh! You say – as your fingers open to show two blisters which represent the thought card, ‘I would have been burnt for this 300 years ago!’ (1).

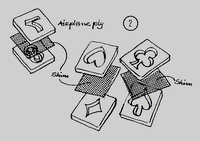

Make up some gimmicks in airplane ply by cutting or burning out the indices of cards (2). Stick them together in pairs and assemble them as an index with perhaps a magnet added as (3).

Placing (say) pairs together so that only two gimmicks have to be stolen out of an eight section index to render any playing card.

You do this by placing two tabs together and squeezing between the second finger and thumb. Raise a fake blister on both fingers allowing the tabs to drop into a finger palm where they remained concealed (1).

Monday, June 05, 2006

OPEN AND SHUT CASE

This item was previously published in New Talon number 3. It was inspired by Jack Yates’ effect Clue from his book Clue and other Miracles. It can be presented as a murder mystery game. But my main reason for describing it here is to highlight the method, which might interest anyone familiar with those logic puzzles featuring liars and truth-tellers.

Effect: The performer invites six spectators play the part of suspects in a game of murder. One of them is a murderer but only the murderer knows that. Three of them are compulsive liars. Fortunately the other three always tell the truth. The task of the performer is to navigate his way through this maze of deceit and correctly identify the murderer. Naturally, he always does.

Method: I’ll just describe the bare bones of the method. If you like the idea, you’ll find ways of dressing it up and devising an entertaining presentation. To perform the trick you’ll need six blank cards. On three of them write the word LIAR. On the other three write the word TRUTH. You’ll also need a bag (cloth or paper), five white counters and one black counter.

Arrange the cards so that they alternate TRUTH, LIAR, TRUTH, LIAR, TRUTH, LIAR. Put the counters in the bag. Get yourself six volunteers and you are all ready to go.

Bring out the cards. Display a couple of them to show that some of them bear the word LIAR while others contain the word TRUTH. Don’t mention anything about there being an even distribution of LIAR and TRUTH. And don’t reveal the fact that the words alternate. You may indulge in a brief false shuffle but if you do make it a casual looking one.

Arrange your six volunteers in a line. Get the attention of the first volunteer and show him how to cut the cards and complete the cut. Make sure he understands the procedure and then hand him the cards face down. Tell him to put the cards behind his back and give the cards a cut. And then another one. As he does this take out the cloth bag.

When he’s finished cutting the cards, ask him to take the top card of the packet and pass the remainder of the cards to the next volunteer. The second volunteer takes the new top card of the packet before passing the packet on to the third volunteer. Each volunteer takes a card from the top and then passes the cards on until all six volunteers have a card each.

Tell the volunteers to take a peek at the card they are holding. The cards tell them which roles they should play. They will either be a truth teller or a liar. You must really hammer it home that if the volunteer is to play the part of a liar he must lie all the time. It doesn’t matter what he says as long as it is a lie. On the other hand good liars tell lies that can be believed. The opposite applies to the truth-tellers. You cannot overemphasise this. So make it part of your presentation, talking about the compulsive liars and truth-tellers that are part of this story.

Look away while the volunteers peek at their cards. They can put the cards away when they’ve noted their role in the game. Explain that each volunteer will be asked to reach into the bag and pull out one of the counters. Whoever draws the black counter will play the part of the murderer.

The bag is passed from one volunteer to another so that they can draw counters. They hold the counters in their closed fists. Then, when everyone has one, you turn away and the volunteers look at the counters noting whether or not they have the black one. No one allows anyone else to see which counter they have. Only the person with the black counter knows that he or she will play the role of the murderer in this game. The counters are placed out of sight with the cards.

Let’s review the situation. You can’t possibly know who the liars are and who the truth-tellers are. And there is no way for you to know who chose the black counter so you don’t know who the murderer is either. And yet that is precisely what you are going to reveal. And you can do it with one simple question to each volunteer.

Example 1: Let’s assume that the third volunteer in the line of six is the murderer. Let’s also assume that because of the prearrangement of the cards the line alternates TLTLTL, which makes the third volunteer a truth-teller. If you ask each volunteer, “Do you know who the murderer is?” you would get the following yes or no answers: No, Yes, Yes, Yes, No, Yes.

You can see a pattern emerge. There is a block of three ‘yes’ answers. The middle volunteer of any block of three similar answers (in this case it happens to be ‘yes’) will be the murderer. It always works. If the alternation of the cards had made the third person in the line a liar, then you would have a block of three ‘no’ answers and the middle volunteer of this block would be the murderer.

You can also deduce that if the block of three answers is ‘yes’ then the murderer is a truth-teller. If ‘no,’ then the murder is a liar.

Example 2: The block of three might be split by the end of the line but if you are familiar with any kind of stack you will still be able to pick out the block of three. For instance, if the first volunteer in the row is the murderer and the row alternates LTLTLT then the answers to your question will be No, No, Yes, No, Yes, No. The block of three is split but it should be clear that the first volunteer is the middle one of the split block.

By asking only one question of each spectator you can instantly identify the murderer. When presenting the effect it’s best not to ask the key question, ‘Do you know who the murderer is?’ immediately. Instead, give the volunteers time to get into their roles of liars and truth-tellers. If you are presenting this as a murder mystery party you might ask them to think about what they had for dinner. Or to drink. And warn them that in a moment you will ask them a question and that the truth-tellers will always tell the truth but the liars will always lie. Then make good on your promise by asking what each of them what they had for dinner. Make light of the various answers you receive.

You now ask each of them the key question. But do it at random. Don’t just go along the line. Remember who gave what answer. Spot the block of three and deduce who the murderer is and whether they told the truth or a lie. In the finale you first reveal whether the murderer is a liar (a double sin) or a truth-teller. And then go on to identify him or her. It’s as simple as that but as with everything it will only be as entertaining as your presentation. So dress the routine as best you can.

Notes: Although you are looking for a block of three similar answers you can, in some circumstances, identify the murderer from questioning as few as three volunteers. Take Example 2. You only need answers from the first three volunteers (No, No, Yes) to tell you that the first volunteer is the murderer. That’s because if you hit two similar answers you are already in the block of three. Now you can ask the rest of the group completely different questions. It’ll confuse any clever puzzle-savvy folk trying to work out the method.

Need I mention that once you understand the basic principle you can improvise using a deck of playing cards and other items rather than having specially made cards, counters and bag? It makes a good impromptu party trick. Provided everyone is sober!

This item was previously published in New Talon number 3. It was inspired by Jack Yates’ effect Clue from his book Clue and other Miracles. It can be presented as a murder mystery game. But my main reason for describing it here is to highlight the method, which might interest anyone familiar with those logic puzzles featuring liars and truth-tellers.

Effect: The performer invites six spectators play the part of suspects in a game of murder. One of them is a murderer but only the murderer knows that. Three of them are compulsive liars. Fortunately the other three always tell the truth. The task of the performer is to navigate his way through this maze of deceit and correctly identify the murderer. Naturally, he always does.

Method: I’ll just describe the bare bones of the method. If you like the idea, you’ll find ways of dressing it up and devising an entertaining presentation. To perform the trick you’ll need six blank cards. On three of them write the word LIAR. On the other three write the word TRUTH. You’ll also need a bag (cloth or paper), five white counters and one black counter.

Arrange the cards so that they alternate TRUTH, LIAR, TRUTH, LIAR, TRUTH, LIAR. Put the counters in the bag. Get yourself six volunteers and you are all ready to go.

Bring out the cards. Display a couple of them to show that some of them bear the word LIAR while others contain the word TRUTH. Don’t mention anything about there being an even distribution of LIAR and TRUTH. And don’t reveal the fact that the words alternate. You may indulge in a brief false shuffle but if you do make it a casual looking one.

Arrange your six volunteers in a line. Get the attention of the first volunteer and show him how to cut the cards and complete the cut. Make sure he understands the procedure and then hand him the cards face down. Tell him to put the cards behind his back and give the cards a cut. And then another one. As he does this take out the cloth bag.

When he’s finished cutting the cards, ask him to take the top card of the packet and pass the remainder of the cards to the next volunteer. The second volunteer takes the new top card of the packet before passing the packet on to the third volunteer. Each volunteer takes a card from the top and then passes the cards on until all six volunteers have a card each.

Tell the volunteers to take a peek at the card they are holding. The cards tell them which roles they should play. They will either be a truth teller or a liar. You must really hammer it home that if the volunteer is to play the part of a liar he must lie all the time. It doesn’t matter what he says as long as it is a lie. On the other hand good liars tell lies that can be believed. The opposite applies to the truth-tellers. You cannot overemphasise this. So make it part of your presentation, talking about the compulsive liars and truth-tellers that are part of this story.

Look away while the volunteers peek at their cards. They can put the cards away when they’ve noted their role in the game. Explain that each volunteer will be asked to reach into the bag and pull out one of the counters. Whoever draws the black counter will play the part of the murderer.

The bag is passed from one volunteer to another so that they can draw counters. They hold the counters in their closed fists. Then, when everyone has one, you turn away and the volunteers look at the counters noting whether or not they have the black one. No one allows anyone else to see which counter they have. Only the person with the black counter knows that he or she will play the role of the murderer in this game. The counters are placed out of sight with the cards.

Let’s review the situation. You can’t possibly know who the liars are and who the truth-tellers are. And there is no way for you to know who chose the black counter so you don’t know who the murderer is either. And yet that is precisely what you are going to reveal. And you can do it with one simple question to each volunteer.

Example 1: Let’s assume that the third volunteer in the line of six is the murderer. Let’s also assume that because of the prearrangement of the cards the line alternates TLTLTL, which makes the third volunteer a truth-teller. If you ask each volunteer, “Do you know who the murderer is?” you would get the following yes or no answers: No, Yes, Yes, Yes, No, Yes.

You can see a pattern emerge. There is a block of three ‘yes’ answers. The middle volunteer of any block of three similar answers (in this case it happens to be ‘yes’) will be the murderer. It always works. If the alternation of the cards had made the third person in the line a liar, then you would have a block of three ‘no’ answers and the middle volunteer of this block would be the murderer.

You can also deduce that if the block of three answers is ‘yes’ then the murderer is a truth-teller. If ‘no,’ then the murder is a liar.

Example 2: The block of three might be split by the end of the line but if you are familiar with any kind of stack you will still be able to pick out the block of three. For instance, if the first volunteer in the row is the murderer and the row alternates LTLTLT then the answers to your question will be No, No, Yes, No, Yes, No. The block of three is split but it should be clear that the first volunteer is the middle one of the split block.

By asking only one question of each spectator you can instantly identify the murderer. When presenting the effect it’s best not to ask the key question, ‘Do you know who the murderer is?’ immediately. Instead, give the volunteers time to get into their roles of liars and truth-tellers. If you are presenting this as a murder mystery party you might ask them to think about what they had for dinner. Or to drink. And warn them that in a moment you will ask them a question and that the truth-tellers will always tell the truth but the liars will always lie. Then make good on your promise by asking what each of them what they had for dinner. Make light of the various answers you receive.

You now ask each of them the key question. But do it at random. Don’t just go along the line. Remember who gave what answer. Spot the block of three and deduce who the murderer is and whether they told the truth or a lie. In the finale you first reveal whether the murderer is a liar (a double sin) or a truth-teller. And then go on to identify him or her. It’s as simple as that but as with everything it will only be as entertaining as your presentation. So dress the routine as best you can.

Notes: Although you are looking for a block of three similar answers you can, in some circumstances, identify the murderer from questioning as few as three volunteers. Take Example 2. You only need answers from the first three volunteers (No, No, Yes) to tell you that the first volunteer is the murderer. That’s because if you hit two similar answers you are already in the block of three. Now you can ask the rest of the group completely different questions. It’ll confuse any clever puzzle-savvy folk trying to work out the method.

Need I mention that once you understand the basic principle you can improvise using a deck of playing cards and other items rather than having specially made cards, counters and bag? It makes a good impromptu party trick. Provided everyone is sober!

Friday, March 17, 2006

SYMPATHETIC CARDS FROM POCKET

Jesse Demaline had some very clever effects in The Magic Wand magazine but his Sympathetic Cards from Pocket (issue 254) may have been overlooked because of a typo in the article. It’s an intriguing effect. A diabolically simple method. And holds lots of potential for individual variation. Read on.

Effect: Imagine having three cards selected from a blue-backed deck. They are free selections and you really have no idea what cards are being chosen. Meanwhile, a second spectator is shuffling a red-backed deck of cards. They hand it to you and you place it in your jacket pocket.

Now for the magic; you reach inside a remove a card from the shuffled red-backed deck. Amazingly, it matches the first selection. You repeat the feat, pulling out another card and revealing that this one matches the second selection. Finally, you pull out a third card. And yes, it matches the third selection.

Method: It's a great effect and not difficult to do but I bet the method will disappoint you. That would be a pity, because it really is such a good routine. Here goes:

It all depends on using a Mene Tekel Deck. I can hear half of you crying "No!" and the other half wondering what the devil a Mene Tekel Deck is. To be honest it's not much used these days. It is a gimmicked deck consisting of twenty-six different cards and their duplicates. The cards are arranged in pairs and the rear card of each pair has been trimmed a little shorter than its mate. It's similar in construction to the more popular Svengali deck. You'll find more about the Mene Tekel Deck in Hugard's Encyclopedia of Card Tricks, if you're interested.

For this effect let's assume that the Mene Tekel Deck is blue-backed. The red-backed deck is quite ordinary and unprepared and is handed out to a spectator for shuffling. As that is done you bring out the Mene Tekel Deck and give it a few cuts. You can riffle spread the deck face up on the table if you want to show all the cards ordinary, or riffle through them as you would with a Svengali deck. After that you let the cards dribble from the right hand to the left and ask a spectator to call "stop." Stop the dribble action and thumb off the top card of the left portion of the deck and ask him to take it. That will be his selected card.

Because of the construction of the deck, it leaves a duplicate of his card on top of the left portion. Replace this packet on top of the right hand packet, bringing the duplicate to the top of the deck.

Now you go to a second spectator and have another card selected. Again dribble the cards from the right hand and into the left. Ask him to call "stop" at any point and offer him the card stopped at as before. This time you can't cut the deck to bring to the duplicate to the top. Instead, as you bring the right hand packet to the left, you simply thumb over the top card of the left packet and slide the right hand packet below it.

You don't need to make a move out of this. Just do it. If you want to cover it a little, turn to your right as you walk towards the next spectator and at that point ask him to look at his chosen card. As he does, make the move.

Dribble the cards again and ask a third spectator to call "stop." He does and is offered the top card of the left packet. Again, you bring the packets together and slide the new top card of the left portion onto the right portion as it is apparently replaced. If you've done all this correctly, you will have duplicates of each selected card on top of the deck. We're almost there.

Get a break under the top three cards of the deck and palm them into the right hand as you ask the spectator with the red-backed deck to stop shuffling. With the right hand, put the blue-backed deck down on the table. With the left hand, take back the red-backed deck. Transfer it to the right hand and place it into your right jacket pocket. Before the right hand comes out of the pocket, it leaves the palmed cards on top of the deck. The finishing line is in sight.

The rest is just showmanship. To produce the first spectator's card you pretend to fiddle around in your pocket and then bring out the third card down from the top. It's actually got a blue-back, not a red-back, so be careful not to expose it as you show the card and drop it face up onto the table. It matches the first spectator's selection. Similarly the second spectator's selection will be found second card down from the top. And the third spectator's selection will be the top card. Just be careful not to expose the backs as they are produced.

There's not really much more to it. By choreographing the effect properly you will make it easier for yourself. The three spectators who choose cards should be in front of you from left to right. Moving between them will help cover the repositioning of the duplicate cards. The spectator who shuffles the red-backed deck should be on your left. Moving towards him will help cover the palming of the duplicates. It also means it is natural to reach out to him with your left hand and take the deck back.

Final Notes: You can play around with different moves to get the duplicates to the top of the deck but I don't think it is worth complicating it too much. A simple modification you could make is in the loading of the duplicate to the top of the deck. Instead of just pushing the card over the side of the deck, to the right, pull it back with the thumb so that it projects an inch or so at the inner end of the deck. The right hand, now lying by your side, comes up towards the left portion of the deck, hits the injogged card and slides right under it as it is replaced on top of the left portion. It works smoothly and is well covered from the front if the left hand is held high and the deck tipped slightly towards you.

I did experiment with a Mene Tekel Deck arranged so that instead of alternating short/long the pairs alternated long/short. This meant that after a spectator had taken his selection, the duplicate was actually on the face of the upper (right) half of the deck. As the halves were brought together it could be loaded beneath the deck via the Ovette/Kelly move or one of the many variations such as that of Bruce Elliott's in 100 New Magic Tricks. Instead of the duplicates being top-palmed and loaded into the right jacket pocket, they are bottom palmed and deposited in the left. I'm not sure it was any improvement though.

Finally, you can dispense with the palming altogether if you just dip your right hand (and deck) into your right pocket as if opening it ready to receive the red-backed deck. Leave the duplicate cards behind. Put the blue-backed deck away and take the red-backed deck at fingertips and drop it into the pocket alongside the duplicates. The rest is as written.

Jesse Demaline had some very clever effects in The Magic Wand magazine but his Sympathetic Cards from Pocket (issue 254) may have been overlooked because of a typo in the article. It’s an intriguing effect. A diabolically simple method. And holds lots of potential for individual variation. Read on.

Effect: Imagine having three cards selected from a blue-backed deck. They are free selections and you really have no idea what cards are being chosen. Meanwhile, a second spectator is shuffling a red-backed deck of cards. They hand it to you and you place it in your jacket pocket.

Now for the magic; you reach inside a remove a card from the shuffled red-backed deck. Amazingly, it matches the first selection. You repeat the feat, pulling out another card and revealing that this one matches the second selection. Finally, you pull out a third card. And yes, it matches the third selection.

Method: It's a great effect and not difficult to do but I bet the method will disappoint you. That would be a pity, because it really is such a good routine. Here goes:

It all depends on using a Mene Tekel Deck. I can hear half of you crying "No!" and the other half wondering what the devil a Mene Tekel Deck is. To be honest it's not much used these days. It is a gimmicked deck consisting of twenty-six different cards and their duplicates. The cards are arranged in pairs and the rear card of each pair has been trimmed a little shorter than its mate. It's similar in construction to the more popular Svengali deck. You'll find more about the Mene Tekel Deck in Hugard's Encyclopedia of Card Tricks, if you're interested.

For this effect let's assume that the Mene Tekel Deck is blue-backed. The red-backed deck is quite ordinary and unprepared and is handed out to a spectator for shuffling. As that is done you bring out the Mene Tekel Deck and give it a few cuts. You can riffle spread the deck face up on the table if you want to show all the cards ordinary, or riffle through them as you would with a Svengali deck. After that you let the cards dribble from the right hand to the left and ask a spectator to call "stop." Stop the dribble action and thumb off the top card of the left portion of the deck and ask him to take it. That will be his selected card.

Because of the construction of the deck, it leaves a duplicate of his card on top of the left portion. Replace this packet on top of the right hand packet, bringing the duplicate to the top of the deck.

Now you go to a second spectator and have another card selected. Again dribble the cards from the right hand and into the left. Ask him to call "stop" at any point and offer him the card stopped at as before. This time you can't cut the deck to bring to the duplicate to the top. Instead, as you bring the right hand packet to the left, you simply thumb over the top card of the left packet and slide the right hand packet below it.

You don't need to make a move out of this. Just do it. If you want to cover it a little, turn to your right as you walk towards the next spectator and at that point ask him to look at his chosen card. As he does, make the move.

Dribble the cards again and ask a third spectator to call "stop." He does and is offered the top card of the left packet. Again, you bring the packets together and slide the new top card of the left portion onto the right portion as it is apparently replaced. If you've done all this correctly, you will have duplicates of each selected card on top of the deck. We're almost there.

Get a break under the top three cards of the deck and palm them into the right hand as you ask the spectator with the red-backed deck to stop shuffling. With the right hand, put the blue-backed deck down on the table. With the left hand, take back the red-backed deck. Transfer it to the right hand and place it into your right jacket pocket. Before the right hand comes out of the pocket, it leaves the palmed cards on top of the deck. The finishing line is in sight.

The rest is just showmanship. To produce the first spectator's card you pretend to fiddle around in your pocket and then bring out the third card down from the top. It's actually got a blue-back, not a red-back, so be careful not to expose it as you show the card and drop it face up onto the table. It matches the first spectator's selection. Similarly the second spectator's selection will be found second card down from the top. And the third spectator's selection will be the top card. Just be careful not to expose the backs as they are produced.

There's not really much more to it. By choreographing the effect properly you will make it easier for yourself. The three spectators who choose cards should be in front of you from left to right. Moving between them will help cover the repositioning of the duplicate cards. The spectator who shuffles the red-backed deck should be on your left. Moving towards him will help cover the palming of the duplicates. It also means it is natural to reach out to him with your left hand and take the deck back.

Final Notes: You can play around with different moves to get the duplicates to the top of the deck but I don't think it is worth complicating it too much. A simple modification you could make is in the loading of the duplicate to the top of the deck. Instead of just pushing the card over the side of the deck, to the right, pull it back with the thumb so that it projects an inch or so at the inner end of the deck. The right hand, now lying by your side, comes up towards the left portion of the deck, hits the injogged card and slides right under it as it is replaced on top of the left portion. It works smoothly and is well covered from the front if the left hand is held high and the deck tipped slightly towards you.

I did experiment with a Mene Tekel Deck arranged so that instead of alternating short/long the pairs alternated long/short. This meant that after a spectator had taken his selection, the duplicate was actually on the face of the upper (right) half of the deck. As the halves were brought together it could be loaded beneath the deck via the Ovette/Kelly move or one of the many variations such as that of Bruce Elliott's in 100 New Magic Tricks. Instead of the duplicates being top-palmed and loaded into the right jacket pocket, they are bottom palmed and deposited in the left. I'm not sure it was any improvement though.

Finally, you can dispense with the palming altogether if you just dip your right hand (and deck) into your right pocket as if opening it ready to receive the red-backed deck. Leave the duplicate cards behind. Put the blue-backed deck away and take the red-backed deck at fingertips and drop it into the pocket alongside the duplicates. The rest is as written.

Monday, March 13, 2006

So Special

Effect: This is an ambitious card routine using five cards. One of the cards repeatedly rises to the top of the packet. Finally it demonstrates its prowess by penetrating up through the entire deck.

Method: Packet Elevator tricks are not new but this has the distinction of using the double deal as the crux of the method. I was prompted to dig this out of the notebooks after reading Peter Duffie's book Card Conspiracy, where you'll find a number of routines using this sleight. The basic handling is also described in Hugard and Braue's Expert Card Technique, though with a full deck rather than a packet.

Begin by having five cards selected from the deck. Upjog each card as it is pointed to and then strip the five selections out.

Put the deck aside, but within easy reach, and spread the five selected cards between the hands and ask the spectator to choose just one of them.

Give him a pen to sign his name across his selection.

As he signs the card, make a Half Pass of the lower three cards of the four card packet that you are still holding.

Take the pen back and put it away. Then take the signed card and place it face up on what appears to be a face down packet of cards in the hands. You are holding the cards in the left hand dealing grip which is perfect for the double deal.

"The fact that you chosen this card from all the rest gives it a sense of pride. Really. It thinks it's special. Let me show you what I mean."

You apparently turn the signed card face down but in reality you execute a double deal, turning the top and bottom cards over as one. This puts the signed card second from the top.

Remove the top card with the right hand and with the left hand thumb push over the new top card of the packet. Don't spread the packet or you will expose the reversed cards. Now put the 'signed' card below the top card of the packet and square the cards up.

"Let me try to put your card second from the top."

Snap your fingers, do a dance or whatever else it takes to 'make the magic work' and then turn over the top card of the packet to reveal that the signed card has returned to the top.

"You see, it just won't settle for second spot. Thinks it's special. Got to be number one. Let's try again."

Execute another double deal as you apparently turn the signed card face down on top of the packet. Remove the top card face down in the right hand.

"This time we'll place it third from the top."

The left hand thumbs over the top two cards of the packet, again being careful not to expose the reversed card. Place the 'signed' card under the thumbed over cards, pause so that the spectator can appreciate the situation, and then square the packet. Snap your fingers and flip over the top card to show that the signed card has once again returned to the top.

Incidentally, all the turnovers should look alike. Don't use one handling for the double turnover and another when you are flipping over a single card.

"Okay, here's a toughie. This time it goes fourth from the top."

Execute a double turnover to flip the signed card face down. Remove the top card and this time place it fourth from the top of the packet. There are no more reversed cards so you can spread the cards widely when you do this.

Another click of the fingers and you can turn the top card over to show it is the signed card.

"Now this is difficult. Five cards, never been done. Watch."

Genuinely turnover the top card and then place it to the bottom of the packet. You spread the packet to show that it is really being placed there.

To get the card back to the top you execute a double turnover as you apparently flip the top card over. This leaves a face up card hidden under the face up signed card sets you up for the finish.

"Amazing. Almost don't believe it myself but your card can do even better than that. Look."

Execute a double turnover of the top two cards of the packet. Deal the top card, apparently the signed card, face down onto the table. Drop the rest of the packet face down on top of the face down deck which you put aside earlier. Pick the deck up and dribble it face down onto the table 'signed' card.

Ask the spectator to tap the top card of the deck and turn it over himself. He should be surprised to find that it is his signed selection.

And that's it!

Effect: This is an ambitious card routine using five cards. One of the cards repeatedly rises to the top of the packet. Finally it demonstrates its prowess by penetrating up through the entire deck.

Method: Packet Elevator tricks are not new but this has the distinction of using the double deal as the crux of the method. I was prompted to dig this out of the notebooks after reading Peter Duffie's book Card Conspiracy, where you'll find a number of routines using this sleight. The basic handling is also described in Hugard and Braue's Expert Card Technique, though with a full deck rather than a packet.

Begin by having five cards selected from the deck. Upjog each card as it is pointed to and then strip the five selections out.

Put the deck aside, but within easy reach, and spread the five selected cards between the hands and ask the spectator to choose just one of them.

Give him a pen to sign his name across his selection.

As he signs the card, make a Half Pass of the lower three cards of the four card packet that you are still holding.

Take the pen back and put it away. Then take the signed card and place it face up on what appears to be a face down packet of cards in the hands. You are holding the cards in the left hand dealing grip which is perfect for the double deal.

"The fact that you chosen this card from all the rest gives it a sense of pride. Really. It thinks it's special. Let me show you what I mean."

You apparently turn the signed card face down but in reality you execute a double deal, turning the top and bottom cards over as one. This puts the signed card second from the top.

Remove the top card with the right hand and with the left hand thumb push over the new top card of the packet. Don't spread the packet or you will expose the reversed cards. Now put the 'signed' card below the top card of the packet and square the cards up.

"Let me try to put your card second from the top."

Snap your fingers, do a dance or whatever else it takes to 'make the magic work' and then turn over the top card of the packet to reveal that the signed card has returned to the top.

"You see, it just won't settle for second spot. Thinks it's special. Got to be number one. Let's try again."

Execute another double deal as you apparently turn the signed card face down on top of the packet. Remove the top card face down in the right hand.

"This time we'll place it third from the top."

The left hand thumbs over the top two cards of the packet, again being careful not to expose the reversed card. Place the 'signed' card under the thumbed over cards, pause so that the spectator can appreciate the situation, and then square the packet. Snap your fingers and flip over the top card to show that the signed card has once again returned to the top.

Incidentally, all the turnovers should look alike. Don't use one handling for the double turnover and another when you are flipping over a single card.

"Okay, here's a toughie. This time it goes fourth from the top."

Execute a double turnover to flip the signed card face down. Remove the top card and this time place it fourth from the top of the packet. There are no more reversed cards so you can spread the cards widely when you do this.

Another click of the fingers and you can turn the top card over to show it is the signed card.

"Now this is difficult. Five cards, never been done. Watch."

Genuinely turnover the top card and then place it to the bottom of the packet. You spread the packet to show that it is really being placed there.

To get the card back to the top you execute a double turnover as you apparently flip the top card over. This leaves a face up card hidden under the face up signed card sets you up for the finish.

"Amazing. Almost don't believe it myself but your card can do even better than that. Look."

Execute a double turnover of the top two cards of the packet. Deal the top card, apparently the signed card, face down onto the table. Drop the rest of the packet face down on top of the face down deck which you put aside earlier. Pick the deck up and dribble it face down onto the table 'signed' card.

Ask the spectator to tap the top card of the deck and turn it over himself. He should be surprised to find that it is his signed selection.

And that's it!

Sunday, March 12, 2006

Straight to the Point

I think it was Bob Ostin who first showed me how effective this trick could be. You've probably even read it. It is described under the title Round and Round and can be found in Chapter Five of The Royal Road to Card Magic, but it seems to have been overlooked by almost everyone.

The original made use of the Glimpse but that is not used in this version. The mechanics of the trick are almost childish but the timing and presentation turn what is really a very obvious ruse into a real baffler.

Begin by having a deck of cards shuffled and then five cards dealt face down onto the table. Ask a spectator to pick them up and mix them. Tell him to make sure that no one sees any of the cards. When he has finished shuffling, ask him to look at the top card of the packet, remember it, and replace it. You can turn aside while he does this. You want to make the most of the impossible conditions under which this location trick takes place.

"Okay, now put the cards behind your back. You're thinking of a card and I now want you to think of a number too. A simple number from 1 to 5. It's a free choice: 1,2,3,4,5. Chose any one of them and think of it. Got that?"

"I'm going to turn away while you do the next bit because I don't want you to think you're giving me any clues as to what is going on. You're thinking of a card. And you're thinking of a number. Now, whatever that number is, I want you to move that many cards from the top of the packet to the bottom. Do you understand?"

Repeat the instruction if he doesn't.

"Do it silently and slowly so that no one here could possibly know whether you're moving five cards or just one. Let me know when you've finished."

The spectator moves his cards and tells you when he has done.

"Okay, I'm still not looking at you. Will you place the cards face down into my hand."

You extend your hand behind you and take the packet of cards. As soon as you have them, turn to face him, keeping the cards behind your back.

"What I'm going to try and do is imagine I'm you. I'm going to try and imagine I'm thinking of a number and thinking of a card. The same card that you're thinking of."

Look him in the eyes and pretend to concentrate. Really you reverse the order of the cards behind your back and then move two cards from the top of the packet to the bottom. It doesn't matter if anyone sees you moving cards around. You're trying to imagine that you are him so it's reasonable that you will be duplicating his actions.

Suddenly, pretend that something is wrong. Something is not quite right. Turn away from him and hand him the packet of cards behind your back. You've still not looked at any of the cards.

"No, sorry, it's just not happening. Take the cards again. Put them behind you're back. Really think of your card……… Okay. That's it. Now think of your number again. And move that many cards from the top of the packet to the bottom. Do it slowly, do it quietly, don't let anyone know how many cards you're moving. Let me know when you've finished."

He tells you he has finished. You turn around but don't quite face him. Instead you extend your right hand and hold it palm up in front of him.

"Good, now take the top card bring it out and hold it face down above my hand. Keep the other cards behind your back."

He brings the top card out and holds it above your hand.

"Don't let me touch the card."

You don't look at the card either while he is doing this. But you do appear to concentrate and finally, say, "No. Throw it on the table. That's not it."

Ask him to take the next card from the top of the packet and hold it face down above your hand. Concentrate again and finish by saying, "No, that's not it either. Throw it on the table."

He takes a third card from the top of the packet and holds it above your hand. If he's followed the procedure correctly, the third card will be his selection. Trust me, it works. It'll always be the third card down in the packet. Finish by saying, "That's it. That's the one. Would you call out the name of the card you are thinking of?"

He does and you turn to face him. "Turn over the card." He'll be amazed to find that it is indeed the one he has been thinking of.

If you want to short cut the trick even further, ask him to think of the number first and then look at the five cards. He then remembers the card lying at his number from the face of the packet. This way he only moves cards from the top to the bottom of the packet once during the routine. It's a strong trick. You never looked at the cards, you never asked him for his thought of number, and you never touched the cards after he took them back. It's almost a miracle!

Final Notes: Want to tell him his thought of number too? All you need do is nail nick or crimp the top card of the packet before you hand it back. When you come to the revelation, have the third card, his selection, placed aside. Make it clear that's the card you are getting psychic vibes from. But just to make sure have the fourth and fifth cards brought out too, one at a time. You don't get any vibes from them so they go onto the table with the others. I should mention that the discards are dealt into a pile.

Now ask him to name his thought of card. He does and you have him turn that third card, the one placed aside, face up. It is his. He thinks the trick is over. That's your chance to glance down at the cards on the table. When you spot the crimped/nicked card, you can work out the thought of number because it will be that number of cards from the top of the packet. Don't forget to factor the third card into your calculations. Have the spectator concentrate on his number and reveal it in your best Dunninger manner.

I think it was Bob Ostin who first showed me how effective this trick could be. You've probably even read it. It is described under the title Round and Round and can be found in Chapter Five of The Royal Road to Card Magic, but it seems to have been overlooked by almost everyone.

The original made use of the Glimpse but that is not used in this version. The mechanics of the trick are almost childish but the timing and presentation turn what is really a very obvious ruse into a real baffler.

Begin by having a deck of cards shuffled and then five cards dealt face down onto the table. Ask a spectator to pick them up and mix them. Tell him to make sure that no one sees any of the cards. When he has finished shuffling, ask him to look at the top card of the packet, remember it, and replace it. You can turn aside while he does this. You want to make the most of the impossible conditions under which this location trick takes place.

"Okay, now put the cards behind your back. You're thinking of a card and I now want you to think of a number too. A simple number from 1 to 5. It's a free choice: 1,2,3,4,5. Chose any one of them and think of it. Got that?"

"I'm going to turn away while you do the next bit because I don't want you to think you're giving me any clues as to what is going on. You're thinking of a card. And you're thinking of a number. Now, whatever that number is, I want you to move that many cards from the top of the packet to the bottom. Do you understand?"

Repeat the instruction if he doesn't.

"Do it silently and slowly so that no one here could possibly know whether you're moving five cards or just one. Let me know when you've finished."

The spectator moves his cards and tells you when he has done.

"Okay, I'm still not looking at you. Will you place the cards face down into my hand."

You extend your hand behind you and take the packet of cards. As soon as you have them, turn to face him, keeping the cards behind your back.

"What I'm going to try and do is imagine I'm you. I'm going to try and imagine I'm thinking of a number and thinking of a card. The same card that you're thinking of."

Look him in the eyes and pretend to concentrate. Really you reverse the order of the cards behind your back and then move two cards from the top of the packet to the bottom. It doesn't matter if anyone sees you moving cards around. You're trying to imagine that you are him so it's reasonable that you will be duplicating his actions.

Suddenly, pretend that something is wrong. Something is not quite right. Turn away from him and hand him the packet of cards behind your back. You've still not looked at any of the cards.

"No, sorry, it's just not happening. Take the cards again. Put them behind you're back. Really think of your card……… Okay. That's it. Now think of your number again. And move that many cards from the top of the packet to the bottom. Do it slowly, do it quietly, don't let anyone know how many cards you're moving. Let me know when you've finished."

He tells you he has finished. You turn around but don't quite face him. Instead you extend your right hand and hold it palm up in front of him.

"Good, now take the top card bring it out and hold it face down above my hand. Keep the other cards behind your back."

He brings the top card out and holds it above your hand.

"Don't let me touch the card."

You don't look at the card either while he is doing this. But you do appear to concentrate and finally, say, "No. Throw it on the table. That's not it."

Ask him to take the next card from the top of the packet and hold it face down above your hand. Concentrate again and finish by saying, "No, that's not it either. Throw it on the table."

He takes a third card from the top of the packet and holds it above your hand. If he's followed the procedure correctly, the third card will be his selection. Trust me, it works. It'll always be the third card down in the packet. Finish by saying, "That's it. That's the one. Would you call out the name of the card you are thinking of?"

He does and you turn to face him. "Turn over the card." He'll be amazed to find that it is indeed the one he has been thinking of.

If you want to short cut the trick even further, ask him to think of the number first and then look at the five cards. He then remembers the card lying at his number from the face of the packet. This way he only moves cards from the top to the bottom of the packet once during the routine. It's a strong trick. You never looked at the cards, you never asked him for his thought of number, and you never touched the cards after he took them back. It's almost a miracle!

Final Notes: Want to tell him his thought of number too? All you need do is nail nick or crimp the top card of the packet before you hand it back. When you come to the revelation, have the third card, his selection, placed aside. Make it clear that's the card you are getting psychic vibes from. But just to make sure have the fourth and fifth cards brought out too, one at a time. You don't get any vibes from them so they go onto the table with the others. I should mention that the discards are dealt into a pile.

Now ask him to name his thought of card. He does and you have him turn that third card, the one placed aside, face up. It is his. He thinks the trick is over. That's your chance to glance down at the cards on the table. When you spot the crimped/nicked card, you can work out the thought of number because it will be that number of cards from the top of the packet. Don't forget to factor the third card into your calculations. Have the spectator concentrate on his number and reveal it in your best Dunninger manner.

Wednesday, April 13, 2005

Cyclic Aces

This idea was first published in Sorcerer magazine, issue 2 (1988). It’s a simple idea but you might find it useful. It’s also a good excuse for me to try out the OCR software on my new scanner. Let’s hope it works and following is transcribed without too many errors!

Effect: A deck of cards is shuffled, squared and placed in the centre of the table. “It is said that three is a lucky number,” says the performer, “Let’s see if that’s true.” The performer cuts the deck into three packets, stacking one on top of the other and bringing a new card to the top of the deck.

He turns the top card over and it is an Ace. Placing the Ace aside he says, “Well that’s pretty lucky, an Ace.” The performer cuts the cards again, saying, “Of course that’s all it was, pure luck. The odds against doing the same thing again must be pretty phenomenal.” After the cutting the new top card of the deck is turned over and is seen to be another Ace and this is placed with the previously tabled Ace.

The deck is cut again as the performer says, “Three cuts each time, and this is the third time... third time lucky perhaps.” The new top card is turned over and seen to be the third Ace. It’s placed aside, with the first two Aces, and the cutting procedure is repeated.

I should add at this point that the cutting procedure looks incredibly fair, to layman or magician, but despite this, when the new top card is turned over, it is the fourth Ace.

Method: This is more than just an Ace Cutting Routine, it’s a utility principle that you can expand upon and use in many different ways. The whole procedure is made possible by using one crimped card but it’s the novel way in which the crimped card resets itself for each Ace that is of interest. You’ll be glad to know that the trick is entirely self-working.

Place two Aces on top of the deck and the other two, together, about one-third from the face of the deck. crimp the card that lies above the lower pair of Aces. The crimp should be bent downwards and be positioned at the inner right corner of the deck when the deck is tabled face down.

False Shuffle the deck, retaining the positions of the Aces and crimp. An easy way to do this is to cut off the top third of the deck and Riffle Shuffle it into the upper third of the remaining portion. You are Riffle Shuffling above the Crimp and you allow the top two Aces to fall last. This can be repeated several times. You’ll find it even easier if you position the crimp and the Aces below it lower down in the deck before you begin. It will make no difference to the subsequent working.

Spread the deck face down just to show that there are no breaks or whatever and then square it and place it in the centre of the table. You place the deck almost at arm’s length from you. This is for two reasons. Firstly it is a very open gesture; somehow if the deck is away from your body it seems as if there is little you can do in the way of trickery. Secondly it enables you to see your crimp perfectly, a visual check just in case you foul up somewhere along the line.

Reach over and cut approximately one-third of the cards from the top of the deck and place them on the table, beside the original talon. Make a second cut, this time at your crimp, the crimped card becoming the face card of the packet you have just cut. Drop this packet onto the first tabled packet. Pick up the remainder of the deck and drop it on top of the first two portions. Turn over the top card, it will be an Ace.

The cutting can be made to look quite sloppy and effortless, which it almost is, thus adding to the deception. The remarkable thing is that the crimp is again nearly two-thirds down the deck but is now above what were the top two Aces.

Square the deck and repeat the cutting procedure, bringing another Ace to the top and setting the crimp above the third Ace. As each Ace is cut it is laid aside. Cut the deck again, bringing the third Ace to the top and at the same time setting the crimp above the last Ace. Finally cut for the fourth time, bringing the final Ace to the top and revealing it in your most dramatic manner.

Notes: That’s all there is to it but I hope you’ll agree that it is very deceptive and it seems almost impossible to control the Aces during the cuts. The fact that it is self-working should make it easy to use.

Those with a penchant for card handling can of course cull the required Aces to position. You might also like to just locate any pair of cards that happen to be together, position them about one-third in from the face and crimp the card above them as you spread the cards face up in front of you. This leaves only two cards, the other pair, which need to be cut or culled to the top, making your job that little bit easier.

To crimp the card I spread the cards face up between my hands, from left to right, raising them to a vertical position so that only I can see the faces. Having spotted a suitable pair of cards I spread them to the right and use my left thumb to crimp the lower left corner of the card immediately behind them. The left thumb just bends the corner upwards, towards the card’s face.

Vernon’s Aces Ride Again: By reversing the procedure you can use the crimp card to control the aces. In this version you openly places the aces into the deck, apparently at random, and then find them again. Pointless I know but that’s the magic business for you!

Start with the four Aces face up on the table and a crimp card two-thirds of the way down the deck. Cut off about one-third of the deck and table it. Take one of the Aces and drop it onto this packet. Make another cut, this time at the crimp, and drop this packet on top of the just-placed Ace. Pick up the remainder of the deck and drop it on top of the first two cut portions. You’ve secretly placed the crimp above the first Ace while apparently losing the Ace in the deck.

Repeat the procedure, cutting off about a third of the deck and tabling it. Place a second Ace on this portion and then cut another packet from the deck, again making the cut at your crimp, and drop it on top of the Ace. Pick up the remainder of the deck and drop it on top of the first two cut portions.

Repeat this for the third and fourth Aces and you will end up with two Aces on top of the deck and two below the crimped card. By reversing the original procedure you have arrived at the start position for the original Ace Cutting. Reveal the aces in any way you choose.

Not Quite Final Notes: There is more to say on this system but it will only detract from what is offered here. However, when setting up the Aces for cutting (the first routine) you may like to introduce the same sort of ruse that Vernon used in his Cutting the Aces routine (Stars of Magic). You can do this by setting the deck with an Ace on top, followed by a Six-spot, then five indifferent cards, the second Ace, then the rest of the deck with the crimp card set two-thirds of the way down just above the remaining pair of Aces.

Proceed with the first routine, cutting the first, second and third Aces as already explained. When you try to cut the fourth Ace you turn over a Six-spot instead. It looks as if you’ve missed but you recover the situation by explaining that the six in fact tells you that the last Ace is six cards down. Place the Six-spot aside and then deal down six cards from the top of the deck, turning the Ace up on the last card dealt. The extra twist on the fourth Ace brings the routine to a more satisfying conclusion.

If your table space is limited you can always hold the deck in the left hand dealing grip and place the cut off packets on another spectator’s outstretched palm. Ask him to pretend he’s a table and then tap him on the head, knocking on wood for good luck.

A Four Star Discovery: With the deck in the left hand dealing grip and a crimp card a third in from the face, riffle down the outer left corner with the thumb and ask a spectator to call stop. Contrive it so that he halts you when you are about one-third down from the top. Cut this top packet to the table. Push off the new top card of the deck and raise it towards the spectator so that he can remember it. This will be his selection. Drop the selection face down on the tabled packet. Cut at your crimp and drop this packet on top of the selection. Place the remainder of the left hand cards on top of all, burying the selection completely.

Repeat this with three more selections and you will finish up with two selections on top of the deck and two under the crimp. It seems impossible since you do virtually nothing. The cards are in position to be revealed just as in the original Ace Cutting Routine.

However, to add spice to the proceedings try the following:

Hold the deck in the right hand, in position for an Overhand Shuffle with the cards facing left so that you can see them. Note the face card. Let’s imagine it’s a Six-spot. Pull the top and bottom cards off together, into the left hand, mentally counting ‘one’ and then draw off five more cards from the face of the deck, counting each one and bringing your count to ‘six’ which is equal to the noted card. The drawn off cards are shuffled on top of the original milked pair.

Drop the remainder of the deck on top and continue with any False Shuffle or Cut which retains the deck order. You can now cut to three of the selections, just as in the original routine. On cutting the fourth selection you will turn up the Six-spot. It looks like a mistake but you rectify it by dealing six cards off the deck and turning up the final card to reveal the fourth selection. Incidentally the selections will turn up in the reverse order to which they were chosen. That’s all for now. Have fun.

This idea was first published in Sorcerer magazine, issue 2 (1988). It’s a simple idea but you might find it useful. It’s also a good excuse for me to try out the OCR software on my new scanner. Let’s hope it works and following is transcribed without too many errors!

Effect: A deck of cards is shuffled, squared and placed in the centre of the table. “It is said that three is a lucky number,” says the performer, “Let’s see if that’s true.” The performer cuts the deck into three packets, stacking one on top of the other and bringing a new card to the top of the deck.

He turns the top card over and it is an Ace. Placing the Ace aside he says, “Well that’s pretty lucky, an Ace.” The performer cuts the cards again, saying, “Of course that’s all it was, pure luck. The odds against doing the same thing again must be pretty phenomenal.” After the cutting the new top card of the deck is turned over and is seen to be another Ace and this is placed with the previously tabled Ace.

The deck is cut again as the performer says, “Three cuts each time, and this is the third time... third time lucky perhaps.” The new top card is turned over and seen to be the third Ace. It’s placed aside, with the first two Aces, and the cutting procedure is repeated.

I should add at this point that the cutting procedure looks incredibly fair, to layman or magician, but despite this, when the new top card is turned over, it is the fourth Ace.

Method: This is more than just an Ace Cutting Routine, it’s a utility principle that you can expand upon and use in many different ways. The whole procedure is made possible by using one crimped card but it’s the novel way in which the crimped card resets itself for each Ace that is of interest. You’ll be glad to know that the trick is entirely self-working.

Place two Aces on top of the deck and the other two, together, about one-third from the face of the deck. crimp the card that lies above the lower pair of Aces. The crimp should be bent downwards and be positioned at the inner right corner of the deck when the deck is tabled face down.

False Shuffle the deck, retaining the positions of the Aces and crimp. An easy way to do this is to cut off the top third of the deck and Riffle Shuffle it into the upper third of the remaining portion. You are Riffle Shuffling above the Crimp and you allow the top two Aces to fall last. This can be repeated several times. You’ll find it even easier if you position the crimp and the Aces below it lower down in the deck before you begin. It will make no difference to the subsequent working.

Spread the deck face down just to show that there are no breaks or whatever and then square it and place it in the centre of the table. You place the deck almost at arm’s length from you. This is for two reasons. Firstly it is a very open gesture; somehow if the deck is away from your body it seems as if there is little you can do in the way of trickery. Secondly it enables you to see your crimp perfectly, a visual check just in case you foul up somewhere along the line.

Reach over and cut approximately one-third of the cards from the top of the deck and place them on the table, beside the original talon. Make a second cut, this time at your crimp, the crimped card becoming the face card of the packet you have just cut. Drop this packet onto the first tabled packet. Pick up the remainder of the deck and drop it on top of the first two portions. Turn over the top card, it will be an Ace.

The cutting can be made to look quite sloppy and effortless, which it almost is, thus adding to the deception. The remarkable thing is that the crimp is again nearly two-thirds down the deck but is now above what were the top two Aces.

Square the deck and repeat the cutting procedure, bringing another Ace to the top and setting the crimp above the third Ace. As each Ace is cut it is laid aside. Cut the deck again, bringing the third Ace to the top and at the same time setting the crimp above the last Ace. Finally cut for the fourth time, bringing the final Ace to the top and revealing it in your most dramatic manner.

Notes: That’s all there is to it but I hope you’ll agree that it is very deceptive and it seems almost impossible to control the Aces during the cuts. The fact that it is self-working should make it easy to use.

Those with a penchant for card handling can of course cull the required Aces to position. You might also like to just locate any pair of cards that happen to be together, position them about one-third in from the face and crimp the card above them as you spread the cards face up in front of you. This leaves only two cards, the other pair, which need to be cut or culled to the top, making your job that little bit easier.

To crimp the card I spread the cards face up between my hands, from left to right, raising them to a vertical position so that only I can see the faces. Having spotted a suitable pair of cards I spread them to the right and use my left thumb to crimp the lower left corner of the card immediately behind them. The left thumb just bends the corner upwards, towards the card’s face.

Vernon’s Aces Ride Again: By reversing the procedure you can use the crimp card to control the aces. In this version you openly places the aces into the deck, apparently at random, and then find them again. Pointless I know but that’s the magic business for you!

Start with the four Aces face up on the table and a crimp card two-thirds of the way down the deck. Cut off about one-third of the deck and table it. Take one of the Aces and drop it onto this packet. Make another cut, this time at the crimp, and drop this packet on top of the just-placed Ace. Pick up the remainder of the deck and drop it on top of the first two cut portions. You’ve secretly placed the crimp above the first Ace while apparently losing the Ace in the deck.

Repeat the procedure, cutting off about a third of the deck and tabling it. Place a second Ace on this portion and then cut another packet from the deck, again making the cut at your crimp, and drop it on top of the Ace. Pick up the remainder of the deck and drop it on top of the first two cut portions.

Repeat this for the third and fourth Aces and you will end up with two Aces on top of the deck and two below the crimped card. By reversing the original procedure you have arrived at the start position for the original Ace Cutting. Reveal the aces in any way you choose.

Not Quite Final Notes: There is more to say on this system but it will only detract from what is offered here. However, when setting up the Aces for cutting (the first routine) you may like to introduce the same sort of ruse that Vernon used in his Cutting the Aces routine (Stars of Magic). You can do this by setting the deck with an Ace on top, followed by a Six-spot, then five indifferent cards, the second Ace, then the rest of the deck with the crimp card set two-thirds of the way down just above the remaining pair of Aces.

Proceed with the first routine, cutting the first, second and third Aces as already explained. When you try to cut the fourth Ace you turn over a Six-spot instead. It looks as if you’ve missed but you recover the situation by explaining that the six in fact tells you that the last Ace is six cards down. Place the Six-spot aside and then deal down six cards from the top of the deck, turning the Ace up on the last card dealt. The extra twist on the fourth Ace brings the routine to a more satisfying conclusion.

If your table space is limited you can always hold the deck in the left hand dealing grip and place the cut off packets on another spectator’s outstretched palm. Ask him to pretend he’s a table and then tap him on the head, knocking on wood for good luck.

A Four Star Discovery: With the deck in the left hand dealing grip and a crimp card a third in from the face, riffle down the outer left corner with the thumb and ask a spectator to call stop. Contrive it so that he halts you when you are about one-third down from the top. Cut this top packet to the table. Push off the new top card of the deck and raise it towards the spectator so that he can remember it. This will be his selection. Drop the selection face down on the tabled packet. Cut at your crimp and drop this packet on top of the selection. Place the remainder of the left hand cards on top of all, burying the selection completely.

Repeat this with three more selections and you will finish up with two selections on top of the deck and two under the crimp. It seems impossible since you do virtually nothing. The cards are in position to be revealed just as in the original Ace Cutting Routine.

However, to add spice to the proceedings try the following:

Hold the deck in the right hand, in position for an Overhand Shuffle with the cards facing left so that you can see them. Note the face card. Let’s imagine it’s a Six-spot. Pull the top and bottom cards off together, into the left hand, mentally counting ‘one’ and then draw off five more cards from the face of the deck, counting each one and bringing your count to ‘six’ which is equal to the noted card. The drawn off cards are shuffled on top of the original milked pair.

Drop the remainder of the deck on top and continue with any False Shuffle or Cut which retains the deck order. You can now cut to three of the selections, just as in the original routine. On cutting the fourth selection you will turn up the Six-spot. It looks like a mistake but you rectify it by dealing six cards off the deck and turning up the final card to reveal the fourth selection. Incidentally the selections will turn up in the reverse order to which they were chosen. That’s all for now. Have fun.

Monday, March 14, 2005

The Last Game

This poker routine was originally published in The New Talon. It began as an attempt to simplify Karl Fulves’ According to Hoyle, which was published in his The Magic Book, an excellent book now reprinted by Dover as the Big Book of Magic Tricks.

It’s a poker deal with a psychological flavour in which the spectators get the opportunity to switch hands with you during the game yet you always win. Fulves’ effect was great for someone who played poker but the stack was not easily remembered. The following stack is much simpler and you always win with a four-of-a-kind, a hand easily recognised even by non-players. I’ve also added the repeat deal and final blow-off, proving that the spectator just can’t win.

Remove the Ten of Clubs, Ten of Hearts and Ten of Diamonds from the deck and place them in the card case, wallet or anywhere else that you can produce them from later in the routine. The rest of the deck is stacked as follows, from the top:

AS, KS, QS, JS, 10S, AD, KD, QD, JD, X, AH, KH, QH, JH, X, AC, KC, QC, JC, REST OF DECK.

The “X” can be any card.